There’s nothing a man can do that I can’t do better and in heels. –Ginger Rogers

If you want something said, ask a man. If you want something done, ask a woman. Margaret Thatcher

International Women's Day (IWD) is celebrated on the 8th of March every year around the world. It is a focal point in the movement for women's rights.

After the Socialist Party of America organized a Women's Day in New York City on February 28, 1909, German delegates Clara Zetkin, Käte Duncker and others proposed at the 1910 International Socialist Woman's Conference that "a special Women's Day" be organized annually. After women gained suffrage in Soviet Russia in 1917, March 8 became a national holiday there. The day was then predominantly celebrated by the socialist movement and communist countries until it was adopted by the feminist movement in about 1967. The United Nations began celebrating the day in 1977.

Commemoration of International Women's Day today ranges from being a public holiday in some countries to being largely ignored elsewhere. In some places, it is a day of protest; in others, it is a day that celebrates womanhood. On March 8, 1917, on the Gregorian calendar, in the capital of the Russian Empire, Petrograd, women textile workers began a demonstration, covering the whole city. This marked the beginning of the February Revolution, which alongside the October Revolution made up the Russian Revolution.

Women in Saint Petersburg went on strike that day for "Bread and Peace" – demanding the end of World War I, an end to Russian food shortages, and the end of czarism. Revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky wrote, "23 February (8th March) was International Woman's Day and meetings and actions were foreseen. But we did not imagine that this 'Women's Day' would inaugurate the revolution. Revolutionary actions were foreseen but without date. But in the morning, despite the orders to the contrary, textile workers left their work in several factories and sent delegates to ask for support of the strike… which led to mass strike... all went out into the streets." Seven days later, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, and the provisional Government granted women the right to vote.

The earliest Women's Day observance, called "National Woman's Day," was held on February 28, 1909, in New York City, organized by the Socialist Party of America at the suggestion of activist Theresa Malkiel. There have been claims that the day was commemorating a protest by women garment workers in New York on March 8, 1857, but researchers Kandel and Picq have described this as a myth created to "detach International Women's Day from its Soviet history in order to give it a more international origin".

In August 1910, an International Socialist Women's Conference was organized to precede the general meeting of the Socialist Second International in Copenhagen, Denmark. Inspired in part by the American socialists, German delegates Clara Zetkin, Käte Duncker and others proposed the establishment of an annual "Women's Day", although no date was specified at that conference. Delegates (100 women from 17 countries) agreed with the idea as a strategy to promote equal rights including suffrage for women.

The following year on March 19, 1911, IWD (international women's day) was marked for the first time, by over a million people in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire alone, there were 300 demonstrations. In Vienna, women paraded on the Ringstrasse and carried banners honouring the martyrs of the Paris Commune. Women demanded that they be given the right to vote and to hold public office. They also protested against employment sex discrimination. The Americans continued to celebrate National Women's Day on the last Sunday in February. Female members of the Australian Builders Labourers Federation march on International Women's Day 1975 in Sydney.

In 1913 Russian women observed their first International Women's Day on the last Saturday in February (by the Julian calendar then used in Russia).

In 1914, International Women's Day was held on March 8 in Germany, possibly because that day was a Sunday, and now it is always held on March 8 in all countries. The 1914 observance of the Day in Germany was dedicated to women's right to vote, which German women did not win until 1918.

In London there was a march from Bow to Trafalgar Square in support of women's suffrage on March 8, 1914. Activist Sylvia Pankhurst was arrested in front of Charing Cross station on her way to speak in Trafalgar Square. [Men are not against you; they are merely for themselves. -Gene Fowler, journalist and author (8 Mar 1890-1960)]

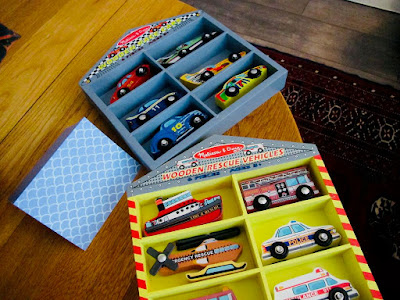

This evening we had supper, [Chef Patrizzio prepared baked chicken breasts, garlic mashed potatoes, butternut squash, ahead of time at The Burn Street Bistro, and a large mixed salad, at Chloë's place], at Winnipeg Street and I was able to take pictures of all the wonderful presents sent by Ariane and Teens. [As I mentioned, in an earlier Facebook post, Chloë will certainly be in touch to thank them both.] Unfortunately, I forgot my camera when we went home and so I wasn't able to download the pictures imediately. Anyway, I'm quite jealous of the fabulous wooden vehicles so I might steal them away when Rowan James is sleeping!

Hi Chuck, Let’t do something at this end of the valley and decide at 9:00 at the IGA. Patrick, can you send a note to interested parties to meet at the IGA at 9:00 am. Bring cleats. Gone for 3 hours and followed by coffee. Thanks, Tim

Hello Monday Cleat-Wearing Boot Hikers! Tall Timber and Chuckerini will lead a boot hike out of Summerland on Monday, March 9th. [Cleats are suggested!] Interested Pentictonites should meet at Cherry Lane at 8:40 am to carpool to the rendezvous point, IGA parking lot in Summerland, by 9:00 am. Onward and Upward! In the spirit of International Women's Day "We Can Do it!" Cheers, Patrizzio! Pics: IWD!

Hi Cleat People! I'm sorry to report that I won't be able to join you tomorrow. Really disappointed as I was looking forward to the hike, especially since last few have been so terrific. It turns out that there are a number of things we have to do, with respect to Chloë's suite, so while you are enjoying the great outdoors I'll be buying paint and running a scad of other errands. Nevertheless, trust you have a most enjoyable outing and will chat anon. I guess we might not see you for more than a week if you are off to Vancouver next week. Cheers, Patrizzio!

Hello Marketing Department, Coffaro Winery! We plan to collect our 2018 futures towards the beginning of May when we will drive to LA to attend Pierre's graduation. As I understand it, this comes with two of David's fabulous pizzas!

Tinsel Towners arrived home safely last night. Must away as we are off to The Home Show shortly. Stay well. Fondestos from Lady Dar to you both. Cheers, Patrizzio! Pics: Return to Penticton!

Betty Friedan's book The Feminine Mystique gave voice to simmering discontent among a generation of women in the 1950s, when it became a cultural norm and expectation for women to set aside their own ambitions to raise children and support their husband's career:

"By the end of the nineteen-fifties, the average marriage age of women in America dropped to 20, and was still dropping, into the teens. Fourteen million girls were engaged by 17. The proportion of women attending college in comparison with men dropped from 47 per cent in 1920 to 35 per cent in 1958. A century earlier, women had fought for higher education; now girls went to college to get a husband. By the mid-fifties, 60 per cent dropped out of college to marry, or because they were afraid too much education would be a marriage bar. Colleges built dormitories for 'married students,' but the students were almost always the husbands. A new degree was instituted for the wives -- 'Ph.T.' (Putting Husband Through).

"Then American girls began getting married in high school. And the women's magazines, deploring the unhappy statistics about these young marriages, urged that courses on marriage, and marriage counselors, be installed in the high schools. Girls started going steady at twelve and thirteen, in junior high. Manufacturers put out brassieres with false bosoms of foam rubber for little girls of ten. And an advertisement for a child's dress, sizes 3-6x, in the New York Times in the fall of 1960, said: 'She Too Can Join the Man-Trap Set.'

"By the end of the fifties, the United States birthrate was overtaking India's. The birth-control movement, renamed Planned Parenthood, was asked to find a method whereby women who had been advised that a third or fourth baby would be born dead or defective might have it anyhow. Statisticians were especially astounded at the fantastic increase in the number of babies among college women. Where once they had two children, now they had four, five, six. Women who had once wanted careers were now making careers out of having babies.

So rejoiced Life magazine in a 1956 paean to the movement of American women back to the home. "In a New York hospital, a woman had a nervous breakdown when she found she could not breastfeed her baby. In other hospitals, women dying of cancer refused a drug which research had proved might save their lives: its side effects were said to be unfeminine. 'If I have only one life, let me live it as a blonde,' a larger-than-life-sized picture of a pretty, vacuous woman proclaimed from newspaper, magazine, and drugstore ads. And across America, three out of every ten women dyed their hair blonde. They ate a chalk called Metrecal, instead of food, to shrink to the size of the thin young models. Department-store buyers reported that American women, since 1939, had become three and four sizes smaller. 'Women are out to fit the clothes, instead of vice-versa,' one buyer said.

"Interior

decorators were designing kitchens with mosaic

murals and original paintings, for kitchens were once again the center

of women's lives. Home sewing became a million-dollar industry. Many

women no longer left their homes, except to shop, chauffeur their

children, or attend a social engagement with their

husbands. Girls were growing up in America without ever having jobs

outside the home. In the late fifties, a sociological phenomenon was

suddenly remarked: a third of American women now worked, but most were

no longer young and very few were pursuing careers.

They were married women who held part-time jobs, selling or secretarial,

to put their husbands through school, their sons through college, or to

help pay the mortgage. Or they were widows supporting families. Fewer

and fewer women were entering professional

work.

The shortages in the nursing, social work, and teaching professions caused crises in almost every American city. Concerned over the Soviet Union's lead in the space race, scientists noted that America's greatest source of unused brainpower was women. But girls would not study physics: it was 'unfeminine.' A girl refused a science fellowship at Johns Hopkins to take a job in a real-estate office. All she wanted, she said, was what every other American girl wanted -- to get married, have four children and live in a nice house in a nice suburb.

"The suburban housewife -- she was the dream image

of the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of women all over

the world. The American housewife -- freed by science and labor-saving

appliances from the drudgery, the dangers

of childbirth and the illnesses of her grandmother. She was healthy,

beautiful, educated, concerned only about her

husband, her children, her home. She had found true feminine

fulfillment. As a housewife and mother, she was respected

as a full and equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose

automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had everything that

women ever dreamed of.

The shortages in the nursing, social work, and teaching professions caused crises in almost every American city. Concerned over the Soviet Union's lead in the space race, scientists noted that America's greatest source of unused brainpower was women. But girls would not study physics: it was 'unfeminine.' A girl refused a science fellowship at Johns Hopkins to take a job in a real-estate office. All she wanted, she said, was what every other American girl wanted -- to get married, have four children and live in a nice house in a nice suburb.

"In the fifteen years after World War II, this mystique of feminine fulfillment became the cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary American culture. Millions of women lived their lives in the image of those pretty pictures of the American suburban housewife, kissing their husbands goodbye in front of the picture window, depositing their stationwagonsful of children at school, and smiling as they ran the new electric waxer over the spotless kitchen floor. They baked their own bread, sewed their own and their children's clothes, kept their new washing machines and dryers running all day. They changed the sheets on the beds twice a week instead of once, took the rug-hooking class in adult education, and pitied their poor frustrated mothers, who had dreamed of having a career.

Their only dream was to be perfect wives and mothers; their highest ambition to have five children and a beautiful house, their only fight to get and keep their husbands. They had no thought for the unfeminine problems of the world outside the home; they wanted the men to make the major decisions. They gloried in their role as women, and wrote proudly on the census blank: 'Occupation: housewife.' The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan, Norton,1997, 1991, 1974, 1963.

No comments:

Post a Comment